My maps aim to be personal and intimate, to examine and challenge power and to embrace uncertainty. They are created from my personal stories and feelings about a place. Hiking through the Growler Valley, I have experienced moments where I am floored by the majesty of the mountains and the diverse personalities of the plants. There have been moments where I wonder if L’Aguja is ever going to get any closer. And times where I am overwhelmed with confusion by the map in my head of water drops, recovery sites, place names and campsites.

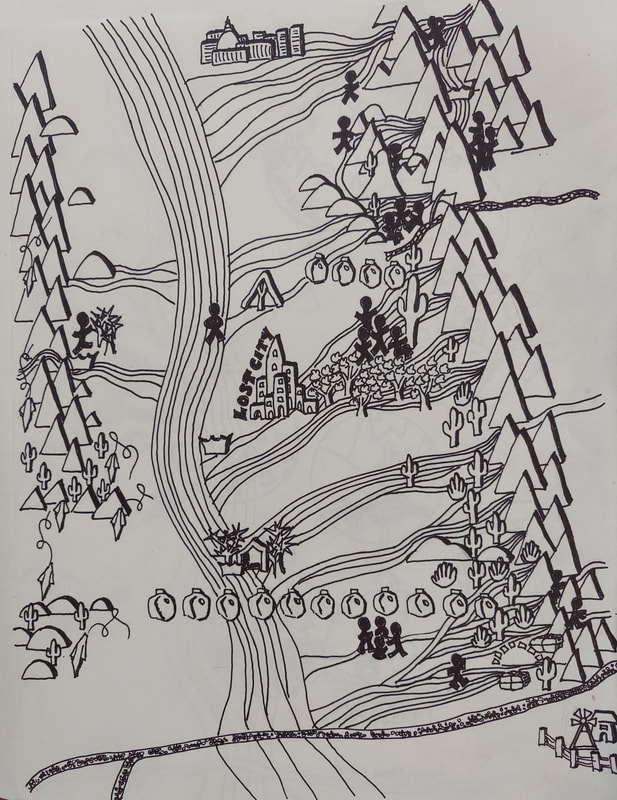

HOW LONG IS THE HIKE?

|

"The step/stride is the ultimate measure of distance." - Jim Enote, A:shiwi cartographer

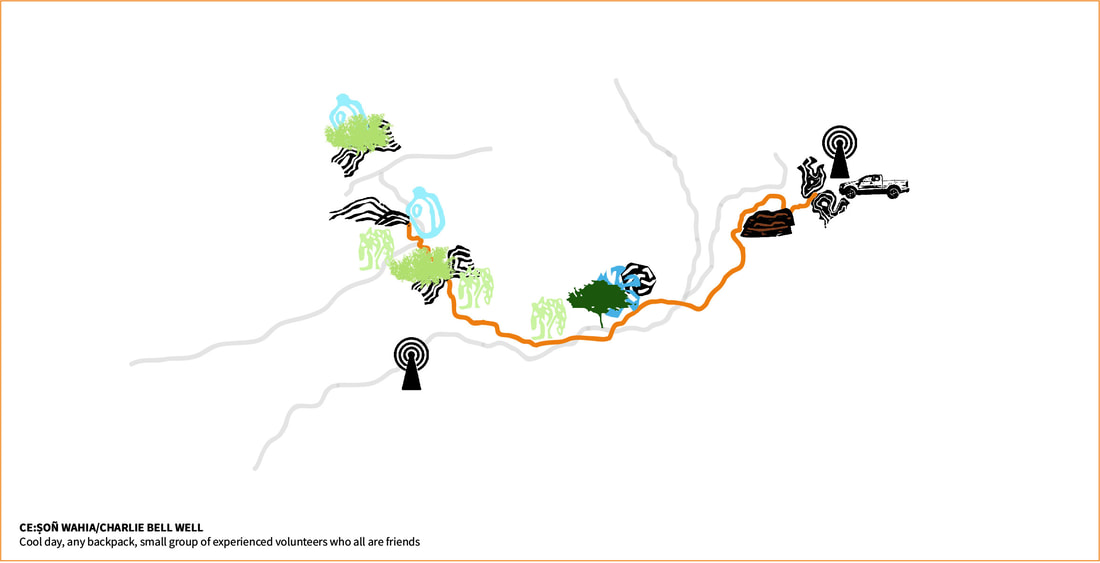

How long is the hike is a ubiquitous and seemingly simple question. The answer is expected to be provided in imperial / US standard miles with an assumption that all miles are equal. When I first came to the desert I suffered from this assumption. It took me about 40 minutes to walk the 1.9 miles to work along Benning Road in DC, therefore when someone said the water drop was 1.5 miles from the truck I figured it would take about 30 minutes to get there. How long the hike is has almost nothing to do with imperial measurements. Distance in the desert for me is measured by the warmth of the sun; my relationship to the land and the people I am with; the weight on my back and in my mind; and by my previous and present experience of the trail. These maps visualize the distance to a water drop near Ce:son Wahia/Charlie Bell Well from the end of the public road at Charlie Bell Pass. Top: On a cool day with a small group of friends Below: In any weather on an emotionally challenging day with a rescue/recovery or injury. |

O'ODHAM WAYS OF MOVING THROUGH THE DESERT

|

Often when I am walking through the desert, following a trail I have the distinct impression that I am on a route that has been walked by people for many years.

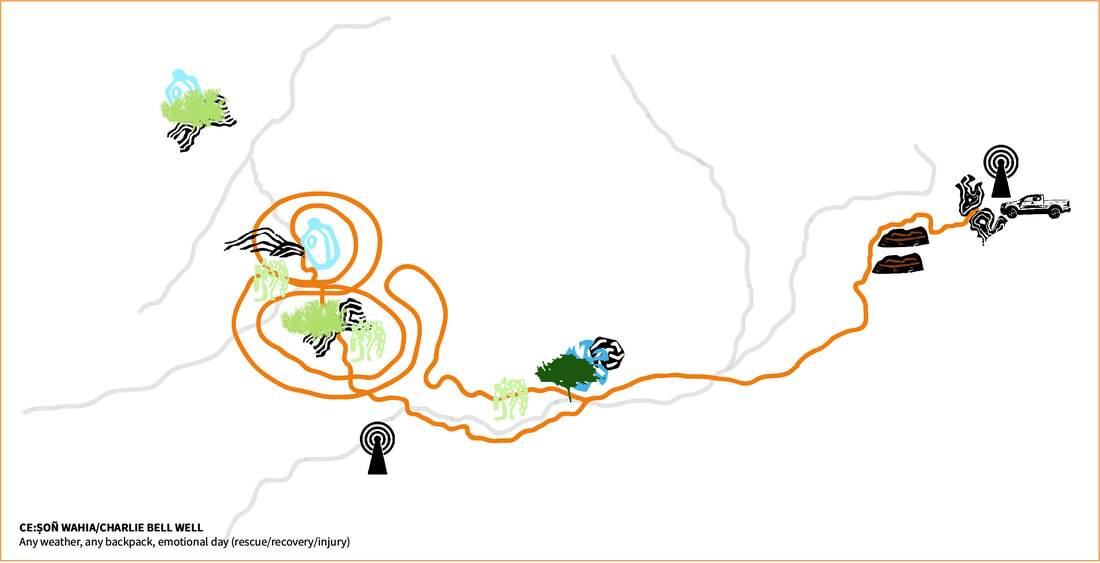

For this map I found the oldest colonial maps I could on the Bureau of Land Management and US Geological Survey websites and looked for the locations of water sources and routes mentioned in O'odham narratives of traveling through the desert. Most of these traditional routes that connect communities, sacred sites, and seasonal villages have been erased by US American roads, the water sources have been dried up and the way blocked by militarized land "management" and international borders. Click here to view the full map |

SEARCH HERE: THE GROWLER VALLEY

|

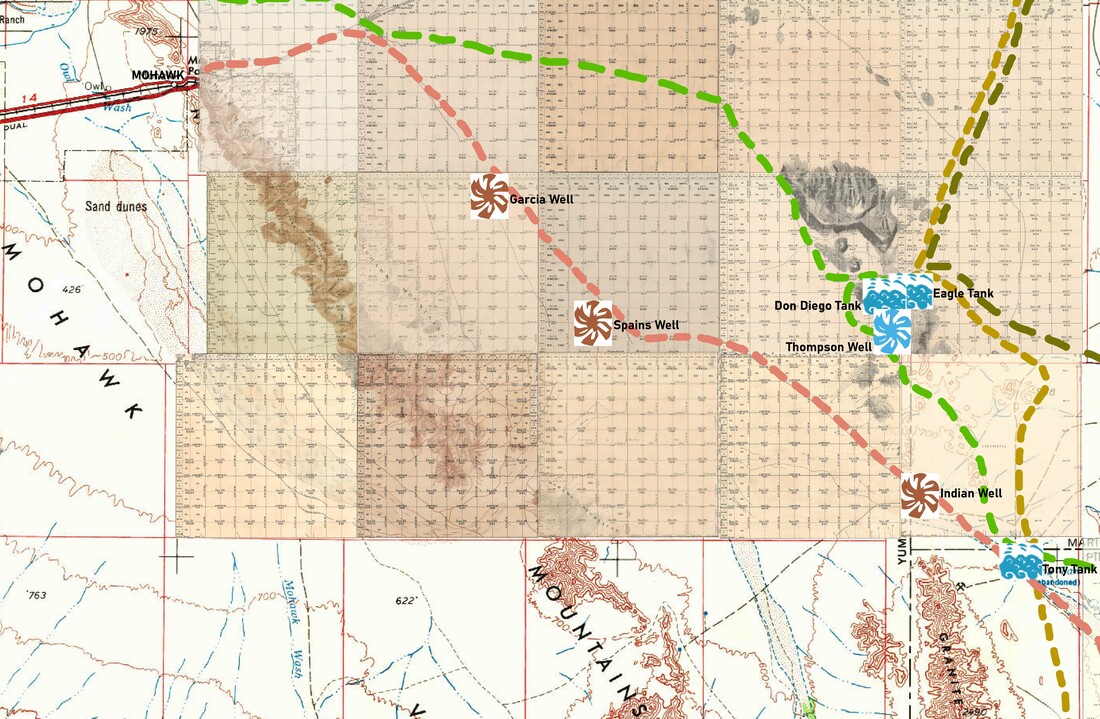

Sometimes when friends or acquaintances ask me what I have been doing at the US/Mexico border I tell them, “humanitarian aid and search and rescue/recovery (SAR).” I know full well that “search and rescue” conjures up images of helicopters, well organized lines of searchers, 4-wheel drive trucks and high-tech navigation equipment. If I were to try and explain the complexity, the “messiness,” of searching for people traveling through the desert it would take hours, their eyes would glaze over and they would start telling me about their latest purchase on Amazon.... Click here to continue reading |

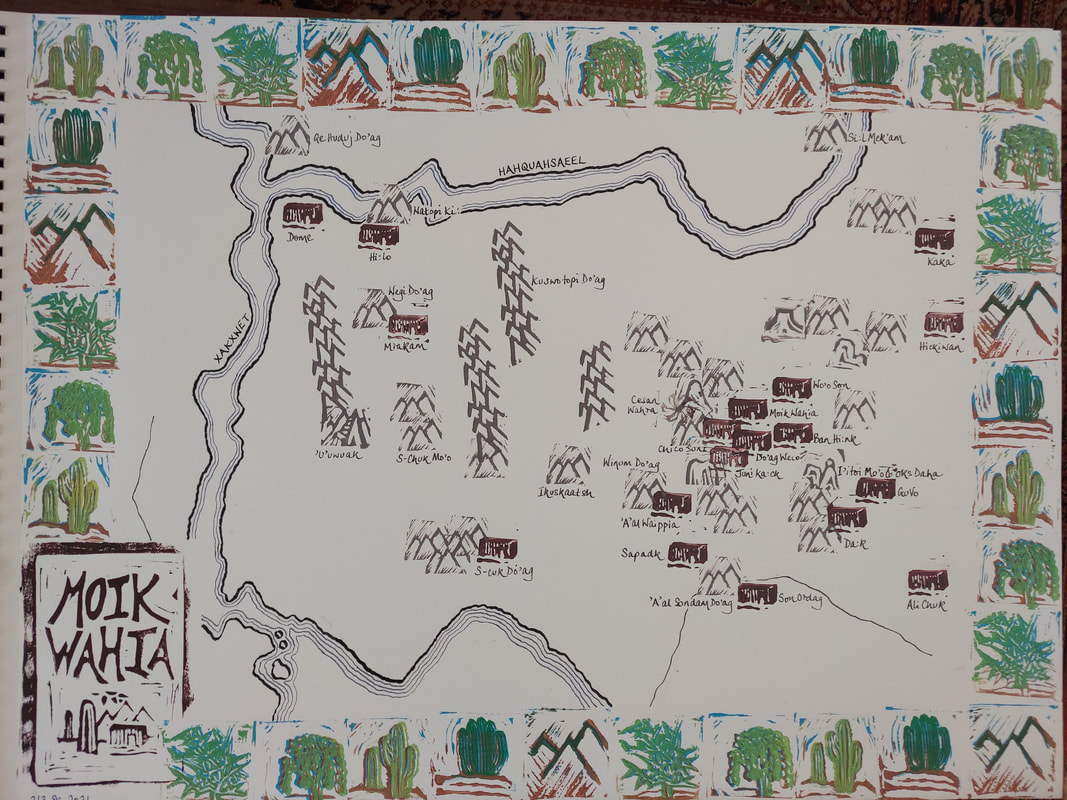

MOIK WAHIA

|

Many times when I have drawn maps of the Sonoran Desert around Ajo to orient new humanitarian aid volunteers to the area I have begun by drawing the US/Mexico border and the borders of the US government land management jurisdictions. In creating this map I began by drawing the water (the Xakxwet and Haquahasaeel rivers) and the communities. My goal was to orient myself around what brings life and inclusion, water and people, rather than artificial and exculsionary boundaries. |

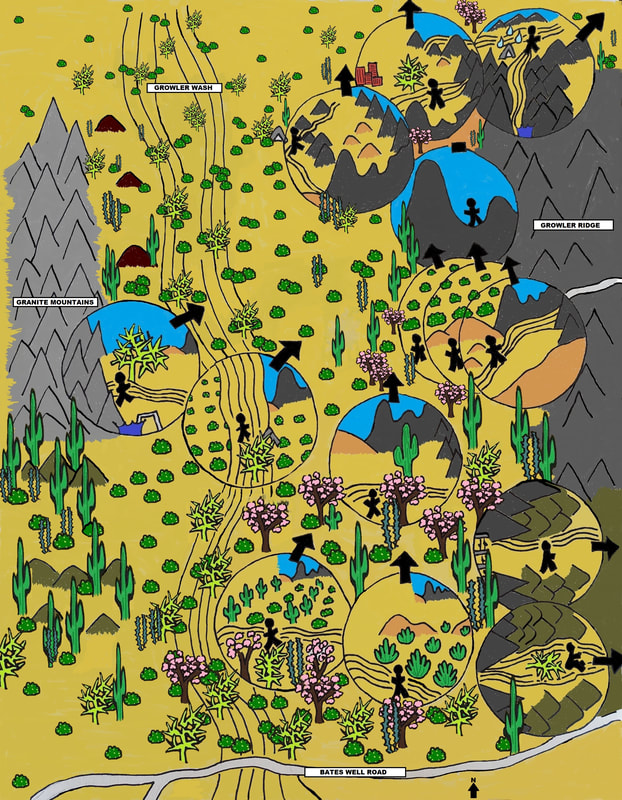

ALL "ROADS" LEAD TO L'AGUJA

|

I created this map of the Growler Valley west of Ajo in response to requests from families of people who have died in the desert for photographs of the view from the place where their loved ones passed. All too often that view is looking North towards "L'Aguja." The map also responds to the "Map of Migrant Mortality," aka "the red dot map," that marks the location where people who have died crossing the desert with a red circle. The "red dot map" reduces people's lives and dreams to a red circle that is all to often used for fundraising and border propaganda. Each magnified circle represents someone who has been found in the desert by a recovery group that I have been a part of. I have tried to show the active agency of their lives. |

LOST CITY

|

There are many "lost cities" in the Growler Valley. One is the physical location of an ancient Hohokam community located somewhere deep in the center of the valley. Another does not have a precise location, its residents have disappeared and died across the valley from the Granite Mountains in the West to the Growler Ridge on the East, and from Bates Well Road in the South all the way north to I8. They were separated from their families, friends and travel companions in life. In death they have found each other as part of the desert. A third "lost city" is the "Bombing Range Tactical Village", where the US military practices for taking its wars to cities across the world. It is mainly empty, perhaps a symbol of the emptiness of war, militarization, colonialism and imperialism. |

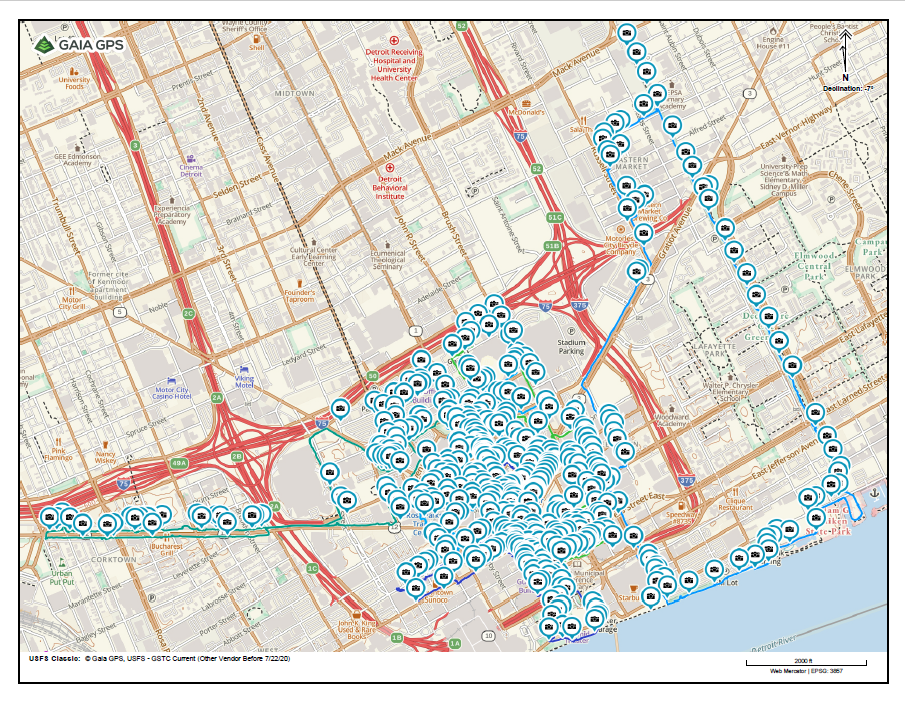

SMILE! YOU'RE UNDER SURVEILLANCE

|

Counter-mapping is mapping against dominant power structures. In this case that power structure is Detroit capitalists. The financial cost of the downtown revitalization to the City’s residents, through subsidies “adding up to billions of dollars in tax incentives, grants, low-interest loans, and cheap land provided by various government entities” to billionaire developers, is widely known. There is another cost, one that is not so well documented, to Detroiters freedom and right to privacy. To show how the City has given away, not only our hard earned dollars, but also access to our souls to Gilbert, Ilitch, and their ilk, I spent a week, with my foster dog, Sheba, walking the streets and marking the location of every street facing private surveillance camera I saw. I mapped 481 cameras in 2 square miles of downtown Detroit. |